Rene Russo and Jake Gyllenhaal in “Velvet Buzzsaw”

“Velvet Buzzsaw” is a horror-comedy that takes place entirely within the contemporary art world. It’s an unusual choice, but since Hollywood has already decided that all art world people are utterly unlikable, why should we care when they start getting killed? Every major character in this 2019 Netflix film is guilty of reprehensible behavior of one kind or another (even the archivist!), so you’re likely to have about as much sympathy for them as a certain federal judge did for Mary Boone last week.

First, there’s Josephina (Zawe Ashton), a wannabe art dealer who’s stuck working a thankless job as an assistant at a blue chip gallery in LA. When her reclusive neighbor (named Ventril Dease) suddenly passes away, she discovers he was a prolific painter and has left behind his life’s work, stashed in his apartment. Before his instructions to destroy it can be carried out, Josephina swipes it, hoping to jumpstart her career.

Zawe Ashton, product placement in “Velvet Buzzsaw”

She shows the work to her friend Morf Vandewalt (Jake Gyllenhaal), a moody art critic who uses words like “mesmeric” and whose opinion seems to tip the scale between success and failure for any artist showing in Los Angeles. “I’m ensorcelled,” he gushes, and tells her there’s “massive” market for her pile of paintings.

Once news of her discovery gets out, Josephina’s boss, Rhodora (Rene Russo), immediately strong-arms her into relinquishing Dease’s paintings. Offering her a cut of the sales, the two form a reluctant partnership as the art world collectively goes NUTS for Dease (don’t say it). When we actually see the paintings, themselves, they don’t seem particularly contemporary and basically resemble a cross between 19th century Post-Impressionism and illustrations from a children’s book.

Jake Gyllenhaal being “ensorcelled”

Unfortunately for everyone involved, a series of mysterious and unexplained deaths casts a shadow on this newfound sensation. Hands reach out of art installations and strangle people, drawings cause automobile accidents, and paintings absorb victims into the picture. Sometimes it’s Dease’s art and other times it isn’t. There’s really no rhyme or reason to any of it, except we’re led to believe that it’s all happening because the artist spent time in a mental institution and painted with blood. We know this is true because sometimes the dried up blood spontaneously liquifies and oozes down the canvas.

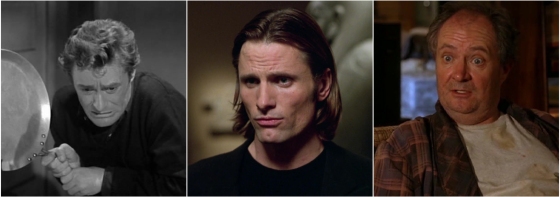

Billy Magnussen pays the price for handling art in “Velvet Buzzsaw”

None of it is scary or suspenseful, and perhaps the film would have worked better purely as a comedy. The art world deserves a good lampooning every once in a while, but viewers might instead look to a film like “Untitled” from 2009. Its critique is just as harsh, but the writers have included some likeable characters we might actually end up empathizing with.

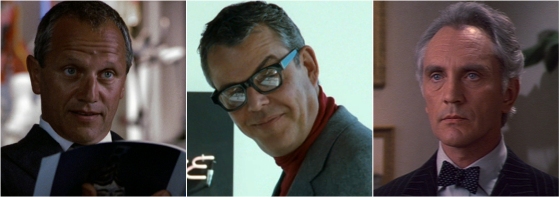

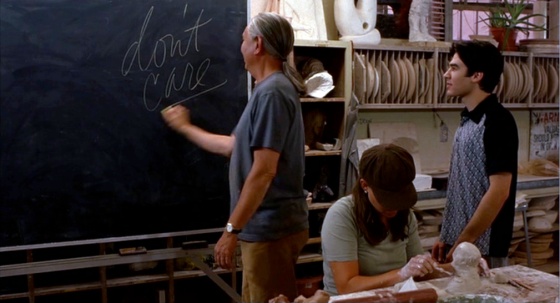

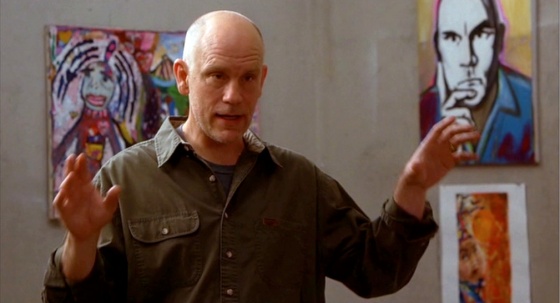

One thing that most art-world-centered plots have in common is the propagation of ridiculous stereotypes. John Malkovich’s character in “Velvet Buzzsaw” is a washed-up abstract artist who makes paintings of drippy blobs, and whose career takes a nosedive after getting sober. If this sounds familiar, you might remember his similar performance in the 2006 film “Art School Confidential,” where he played another washed-up abstract artist who painted only triangles.

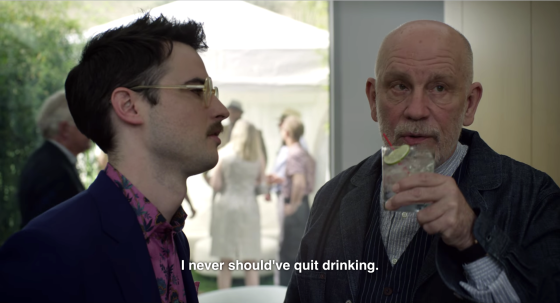

Tom Sturridge and John Malkovich in “Velvet Buzzsaw”

Toni Collette appears as a colluding art dealer who threatens the careers of those standing in her way (she also channels Amy Poehler in a recent Old Navy commercial). Other unsavory types on hand include a bratty rich kid turned gallery owner (Tom Sturridge), a bro-ey art handler who hits on his coworkers and steals (Billy Magnussen) and a tattling gallery assistant who uses gossip for her own career advancement (Natalia Dyer). All it really adds up to is the unambiguous moral revelation that greed is bad and these people should be punished.

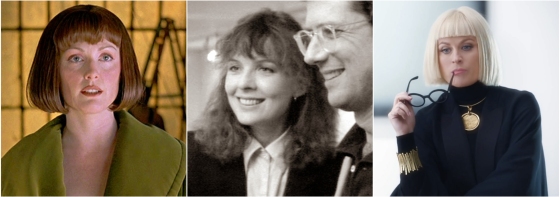

Toni Collette in “Velvet Buzzsaw”

It seems all but impossible for screenwriters to place a storyline in the center of the contemporary art world without presenting it as a caricature. Its impermeability has long served as a valuable narrative tool to alienate the viewer from characters we’re meant to hate. When the business they’re mixed up in seems arbitrary, silly and deceitful, it’s easy to stoke the misgivings of the “My kid could do that” naysayer. But, in turn, perhaps obfuscation is just as precious to art world inductees who fancy themselves as members of an elite class. After all, if you’re not in on the joke, you’re not invited to the after-party.

Rene Russo speaks truth in “Velvet Buzzsaw”