Caden Cotard (Philip Seymour Hoffman) is a theater director living in Schenectady with his wife, Adele Lack (Catherine Keener), who is a painter. Though Caden has enjoyed some acclaim for his work, Adele has no respect for him as an artist and even fantasizes about his dying, freeing her to start over. Having sewn the seeds of doubt in Caden’s mind, Adele goes to Berlin, taking their daughter, Olive, with her. When they leave, Caden gradually starts to die.

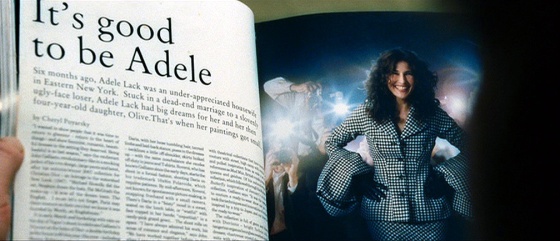

They never return, and though she is absent for the remaining three quarters of the film, Adele and her creative success loom over Caden like something he once read about in a book, but never really knew. His health deteriorating (he suffers from pustules, malfunctioning pupils and seizures), he sees an Elle magazine exposé in the doctor’s office waiting room about Adele’s thriving career. “When I look I see. When I see, I paint. It’s that simple,” she says, and, “I’m at a point in my life where I only want to be around joyous, healthy people.” He tries in vain to reach her on the phone, but she can’t hear him and hangs up, saying, “I have to go, I’m sorry. There’s a party—I’m famous!”

“It’s good to be Adele. Six months ago, Adele Lack was an under-appreciated housewife in Eastern New York. Stuck in a dead-end marriage to a slovenly, ugly-face loser, Adele Lack had big dreams for her and her then four-year-old daughter, Olive. That’s when her paintings got small.”

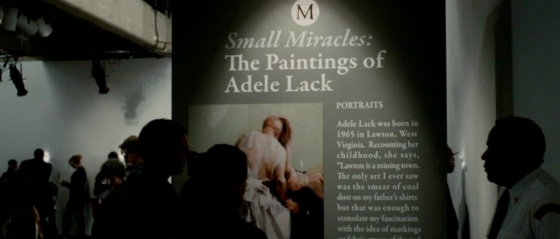

Adele’s paintings are minuscule portraits, created for the film by Russian-born artist Alex Kanevsky. They are so small that one must wear magnifying glasses to view them, and she ships them in miniature crates that look as if they were made for a dollhouse. It’s a visual joke that counters the heroic, macho scale adopted by many New York painters, and their size can be seen as both a metaphor and a marketing gimmick.

After Caden receives a MacArthur Foundation “genius grant,” he goes about staging an impossibly ambitious, autobiographical play. The production, which remains in the works for decades, involves a life-size replica of Manhattan and, quite literally, a cast of thousands. Through his epic undertaking, Caden attempts to achieve artistic truth and relevance, the kind of glory he imagines his wife has left him behind for, all the while facing the inevitability of his own death. (His last name, Cotard, is a reference to Cotard’s syndrome, a rare neuropsychiatric disorder in which a person holds a delusional belief that he or she is dead or does not exist.)

For her part, Adele is not only selfish, but downright cruel. She has kidnapped their daughter and the only direct communication she has attempted with Caden in the past twenty years is an impersonal fax instructing him not to read Olive’s diary. She’s also insufferably pretentious. For instance, the biographical wall text at her Met Museum retrospective reads, “The only art I ever saw was the smear of coal dust on my father’s shirts, but that was enough to stimulate my fascination with the idea of markings on fabric, traces of the real world left to linger as memory.” Spare me!

Caden does, in fact, read Olive’s diary, which magically continues to write itself over time. Through it, he pieces together a picture of his family’s new life, while yet another magazine article proclaims Olive the “first child in human history with a full body tattoo.” As the line between Caden’s play and his real life slowly fades, he performs the role of Adele’s housekeeper, named Ellen. He scrubs her toilet when she isn’t home and receives patronizing notes from her, addressing him as Ellen (“Good for you with your grant!”). Neither Olive nor Adele seems aware of Caden’s recent achievement and recognition, but it clearly wouldn’t matter to them if they were.

The portrayal of Berlin as an artistic haven connects to an attitude that was popular around the time the film was produced. The “party” in New York was over, so to speak, and priced-out artists were moving to Berlin to make their work. Now the party in Berlin is over, and the new party is in Detroit or something. While Adele and Olive have moved on to greener pastures, Caden’s fixation on New York seems simultaneously quaint and solipsistic—he wallows in it.

As Adele has risen to celebrity status, Caden has been demoted to an outside observer. His experience of her is mediated through her press coverage, her Berlin gallerist who refuses to give out “personal informations” and finally, his daughter, who now speaks only German and lies dying in a hospital from infected tattoos.

His exclusion from their lives underscores the pain of creative (and sexual) invisibility and the professional (and personal) jealousies that go along with it. Adele’s success seems more desirable to Caden than his own because he is no longer a part of it. Her life in Berlin is full of glamour and sexual freedom (Olive has become a lesbian and her nanny/tattoo artist is her lover). Free from Caden and his suffering, they live the ultimate artistic existence, and are celebrated for it. In their wake, he ultimately becomes his work—an actor in his play—which mirrors his own life and means nothing.